My last post focused on strategies for managing the pasture through the cow and for the cow. This post will focus on direct changes you can make to the pasture to significantly impact growth and output.

I’ll be the first to admit, prior to owning our ranch, I knew little to nothing about managing grass in Southeast Texas. I had to learn (still learning, actually) which weeds I was dealing with, which grass was growing, and how to find the resources to help me fix my problem. I was starting from ground zero on an overgrazed, weed-infested pasture with minimal grass production. Here’s a picture of what I started with:

We closed on our property in August of 2020, and at that time, I became the proud owner of a luscious crop of goat weed. We had some great dove hunting that year, but our 50+ acres was not even supporting my 5 cows at the time. And since we had come from a much smaller facility, I had next to no hay stockpiled to get us through the winter. Needless to say, it was a lean winter. Fortunately, I had chose not to breed my cows that year so their nutrient requirements were lower since they weren’t in lactation. *Hint* See Part I of Herd and Pasture Management as to why I chose to change my herd physiology for the pasture I was moving onto.

The very first thing I did in my sad attempt to start managing the pasture was get out there on our 25 hp tractor with a 4-foot shredder and go to town. You can imagine, I didn’t make a dent in our 20-acre front pasture before I was sunburnt, choking on pollen, and over it. CLEARLY, this was not going to be an effective strategy to get my pasture up to par. I now refer to shredding as another form of broadcast seeding goat weed.

This is all to say, if I can do this, YOU can do this!

Soil Test

A turning point in my pasture management came from attending a pasture and rangeland seminar at the 2021 Beef Cattle Short Course. The first thing you need to do in managing your pasture is to manage your soil. I utilize TAMU Soil Lab for my testing. And at a whopping $12 per sample for a basic test, there is really no excuse not to be utilizing this tool. Here’s the link: TAMU Soil Test Submittal

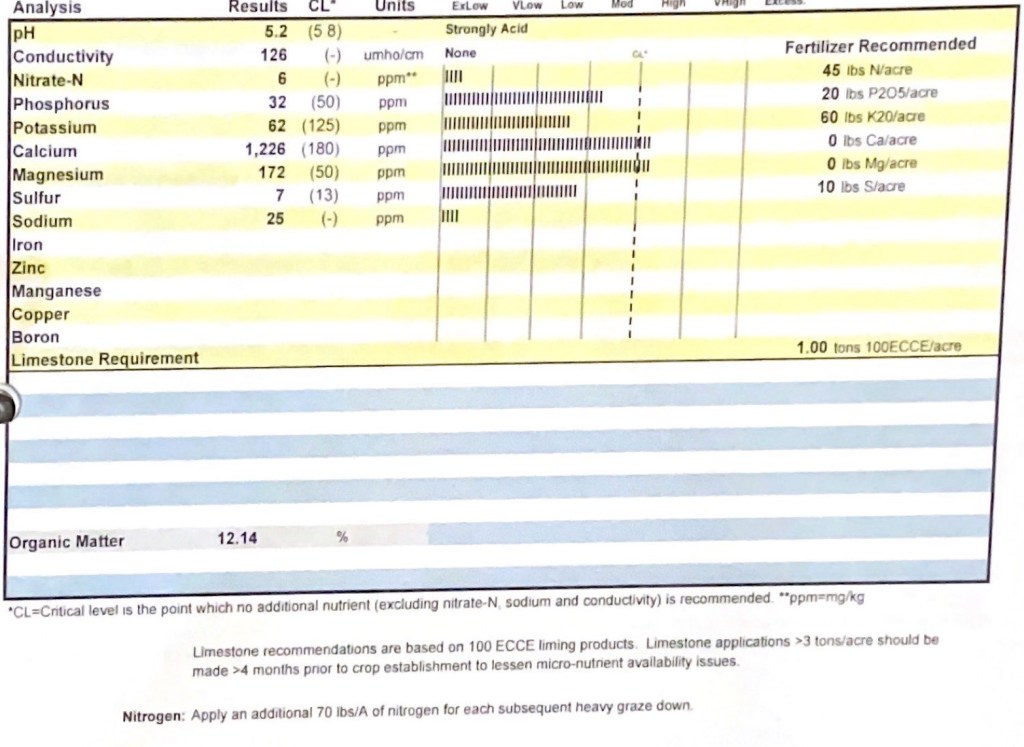

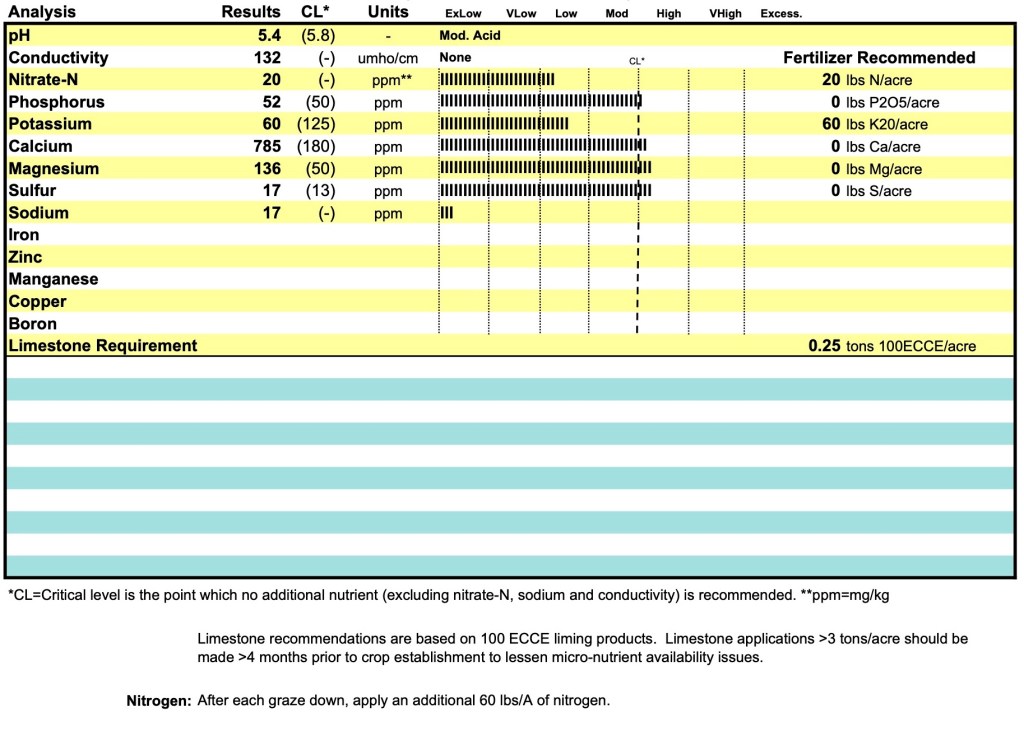

The test not only tells you where the pasture is currently at, but also gives recommendations on how to get it to where it needs to be. Below are my 2021 soil test results (Left) and my 2022 Soil Test results (right). I’ll go over just a few of the highlights from my tests and how I made changes in 2021 to yield the results you see in 2022.

Soil pH

The first line on the soil test deals with soil pH. As you can see in my 2021 test (left), the soil I had was strongly acidic. In our area, we have predominantly sandy loam topsoils, which are generally considered acidic. Highly acidic soil is conducive for weed and pine tree growth; grass growth not so much. To combat this and bring soil pH up, the bottom line of the test has a limestone requirement.

In 2021, I hauled in 21 tons of ag lime at a rate of 1 ton per acre according to what the test suggested. Is this an extreme amount? Yes. Was this what my soil test recommended due to extremely low pH of the soil? Yes. In my eyes, it was money well spent. You can see I brought the pH up from 5.2 to 5.4. Which doesn’t seem like much, but pH is on a logarithmic scale. Meaning a pH of 5.2 is 60% more acidic than a pH of 5.4. Pretty significant change!

Additional Note: I’ve been recommended to put out lime in the Fall, about 60 days before I plant or apply fertilizer. For me, this is August-ish before I overseed with winter grass.

Fertilizer

The same sandy loam soil that is highly acidic, also does a fine job of allowing soil macro- and micro-nutrients to leach out. This means, chances are, your soil is pretty lacking in nutrients and fertilizer applications are a necessity.

Keep in mind, when solely grazing and not cutting for hay, pastures should need fertilizer applications only every 2-4 years depending on grazing intensity. Cows don’t harvest near the nutrients from the pasture that continuous hay production does.

Most fertilizer is reported as a percentage of Nitrogen-Phosphorous-Potassium or N-P2O5-K2O. So, on a 24-6-12 mix, the bag is 24% nitrogen, 6% Phosphorous and 12% Potassium. A GREAT tool for calculating your fertilizer needs is offered by TAMU Here.

The first year I put out fertilizer, I put out 100 lbs/acre of a 24-6-12 fertilizer. This means I put down 24 lbs Nitrogen, 6 lbs of Phosphorous, and 12 lbs of Potassium per acre. I knew I would not balance for Potassium (K), but I was severely deficient in Nitrogen, so that was my main goal. You can clearly see the jump in Nitrogen the following year in 2022 after the initial application.

The second year, I put out 60 lbs/acre of a 25-0-15 fertilizer. This converts to 14 lbs Nitrogen, 0 lbs Phosphorous, and 9 lbs Potassium per acre. I recognize I need to put out an application of Potassium, a.k.a potash, but potash prices are at record highs….so we will hold off for another year or two.

Pesticide Application

If you told me, you only wanted to do 1 single thing to your pasture and you wanted bang for your buck, I would tell you to spray for weeds.

Not only do weeds create nutrient competition (sucking up those expensive fertilizer nutrients), they also compete with your grass for space, sun, and water. Left untouched, they will choke out the grass.

Early in the season, weeds can be sneaky. If you are simply looking for a difference in color, you are likely to miss the ragweed, goat weed, and sneezeweed. They are a bright green and deceive you into thinking you have a healthy pasture, when in fact, there is little to no nutritive value for the cow or horse in them.

Between these 2 pictures, carefully study the shape of the leaf and flowers, and you will see the picture on the left is predominantly weeds, while the right is predominantly grass. Despite both having an appealing green color.

For a comprehensive guide to common weeds in our area (with pictures!), I highly recommend you read this short pamphlet from TAMU Agri-Life: Quick Guide to Weed Management in Pastures and Forages.

Spraying for weeds is something your local feed store can help you with (Huntsville Farm Supply does mine) and comes at a fairly inexpensive cost for the difference it can make. The best time to spray is in the early vegetative stage of the weed, for me, that is typically May. Bear in mind, it may take regular annual sprays to keep your pasture in check. This is especially true for goat weed, which has a hard seed and develops a pretty extensive seed bed once allowed to reach reproductive stage.

The first year, I got on the list a little too late for weed spraying, so it ended up being mid-June when the weeds were in a more mature stage. The second year, I was on top of it and sprayed in May. The knockdown was much better.

It’s money well spent when it doubles, even quadruples, your pasture production. The cost of weed spraying would only buy me 6-8 round bales. That’s a long way from covering my herd’s feed demands for the whole year.

Overseeding

Seed choice and strategy is going to be a whole blog in and of itself. When I write that, I’ll be sure to link it Here. But I think the big takeaway today is to discuss warm and cool season grasses and legumes.

The predominant native grasses we have in Southeast Texas are largely warm-season (March through October-ish) grasses like Bahia grass or Bermuda grass. Many people will overseed with annual rye for their cool season grass (December through March). I talked in-depth in Part I of my series about considerations for those classes of grasses in regard to year-round output and nutrient density for the cow.

You will see in my strategy and results below I have chosen to overseed using a broadcast method with annual rye to cover my forage needs overwinter. This is not my long term strategy, but we are running some test plots to see where I want to spend my money next year. Other cool season mixes, like oats, are 2x as expensive, so I’m working on getting my soil and seeding methodology right before investing into those grasses. I would also like to come in at some point with a warm-season bermuda, like Tifton 85, to increase my warm-season crude protein content of the pasture. Warm-season grasses are even more finicky about taking root, so those will require some testing, too.

The trick to overseeding is to come in at the right time of the year and with the right method (broadcast, scarfiring, scratching, tilling, etc) for your chosen seed. Since rye does well with broadcast (it has a large seed that doesn’t wash away easily), I have been putting it out in late Fall after the first freeze, along with my fertilizer.

Results

On to the moment you’ve been waiting for! My actual real life results. The photo below shows only 1 season of management from where I started in August 2020 to August 2021. If we would have had any rain this past summer, I can only imagine what my 2022 pasture would have looked like.

Here’s exactly what I did and what I paid for our 20-acre Pasture:

6/16/21: Pesticide Application with 6.56 Gallons Grazon, 1 Gallon Li700 – $586

8/27/21: Broadcast 20.6 tons of 100 ECCE Ag Lime – $1237

9/18/21: Broadcast 24-6-12 Fertilizer at 100 lbs/acre – $558

9/18/21: Broadcast Annual Rye at 50 lbs/acre – $700

We were very fortunate to have a good rainy season in 2021, but I still think the results are clear:

Below is what my pasture looked like Fall of 2022 after 2 seasons of management. The results are not as drastic…but we had only 3 inches of rain from May 1 to to September 1 at our place. I think the big takeaway is the lack of weeds and the fact that I have any grass at all. I’d say that is a testament to the soil and pasture health after record drought and record heat. Peep the hay – I was taking my own advice and supplement feeding my cows with round bales.

Leave a comment