This morning, I read an article about the unprecedented reduction in the Nation’s cow herd, particularly in the Southern States (https://southernagtoday.org/2022/11/exceptional-cow-and-heifer-slaughter/)

When there is no grass and feed inputs are expensive, the cow herd gets cut to make ends meet. No one can afford to dry lot a cow-calf operation with calf prices solidly under $150/cwt in our region. The article goes on to suggest there has been a 4-5% national decline in the cow herd, a decline not seen in the last 40 years.

This started my thought process on pasture and cowherd management in our region. While important at all times, pasture management is especially important during environmental stressors, such as drought.

This will be part 1 of a 2-part series addressing management strategies for the pasture and cowherd in Southeast Texas.

Stocking Rate

I’ll start with the most obvious, but possibly most overlooked factor, Stocking Rate.

Stocking rate is considered the amount of animal units (AU) that a given pasture can reasonably accommodate. There are many factors that can influence this, including grazing methods (rotational vs continuous), seeding rate, mixture of grass types, and application of nitrogen to the pasture.

| Standard Animal Units | |||

| AU | AU | ||

| Cow-Calf Pair | 1.35 | Yearlings (12 -15 mo) | 0.7 |

| Non-lactating, mature cow or heifer | 1.0 | Calves (8-12 mo) | 0.6 |

| Yearlings (18-24 mo) | 0.9 | Mature Bull (>24 mo) | 1.5 |

| Yearling (15 -18 mo) | 0.8 | Yearling Bull (18-24 mo) | 1.15 |

In our area, we generally expect 6-7 acres per 1 AU, when using a continuous grazing method on non-improved, native pasture. This varies significantly throughout the year based on grass growth stage, pasture mix, amount of rainfall, and soil conditions. With a wet spring, we can see that reduce to 2 acres/AU throughout the summer, then creep back up to 8+ acres/AU in the winter if no cool season grasses are available.

This means on a typical year, without any supplemental feeding, you can anticipate running 7-8 cows on a 50-acre parcel. This is likely not enough to justify owning cows or enough to meet the appraisal district’s requirements for an ag valuation on property taxes.

So, what can we do to increase this stocking rate? I’m going to list some strategies in order of what I consider to be least to most difficult, taking into consideration both cost and labor.

- Application of Pesticide to reduce weed competition

- Application of Fertilizer to increase grass growth

- Overseeding of cool-season grasses (annual or perennial)

- Supplemental feeding of the cow herd

- Seeding of warm season grasses (requires tilling for maximum result)

- Implementation of fencing for rotational grazing methods

Each operation is different and some of these methods may be easier than others depending on your resources. You’ll notice I listed supplemental feeding of the cow herd with hay and protein much lower on the list than many utilize it. I’ve found it to be very costly, although perhaps easiest when in a pinch, to feed my cows.

At this year’s hay prices of $130+ for a round bale, and bags of cubes near $15, I find this especially difficult to justify.

Nutrient and Protein Requirements of the Cowherd

The last paragraph led quite nicely into my next topic. Why don’t I find supplemental feeding of the cow herd to be a routine and/or economical strategy?

Because a cow eats an enormous amount of feed per day.

We can expect a mature, non-lactating cow to consume between 20 – 25 lbs. of dry matter (DM) per day. Generally, hay is viewed as about 90% DM, meaning 1 lb. of hay provides the cow 0.9 lbs. of dry matter. This DM intake significantly increases when she is in lactation.

| Relationship between As-Fed and Dry Matter Intake of Hay Adapted from Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle, 7th Edition, NRC, 2000 | ||

| Dry Matter (lbs.) | As-Fed (lbs.) | |

| Mature, Non-Lactating Cow | 20-25 | 22-28 |

| Lactating Cow | 25-30 | 28-33 |

| Growing Calf (400 lbs) | 10-12 | 11-13 |

| Yearling (800 lbs) | 20-22 | 22-24 |

Here is my cost breakdown this year per dry cow. It goes up for lactating cows. And I’m fortunate to source extremely good quality hay for a great price and heavy bales.

Usable Hay

(weight of round bale) x (100%- typical waste of 30%) = 1000 lbs. x 70% = 700 lbs.

# of Days/Bale/Cow:

(Usable hay) / (as-fed amount of hay per cow) = 700 lbs / 25 = 28 days

Cost Per day/Cow:

(cost of bale) / (# of days/bale) = $105 / 28 = $3.75/day per cow

This math is for a cow that is in a dry-lot eating nothing but the hay in front of her. Obviously there is a reduction in cost if you also allow pasture access. This year, I’ve seen my 7 cows tackle an 1000 lb round bale in 2 weeks with access to improved pasture. Making their current hay cost over the winter about $1.07/day per cow. Not cheap.

Furthermore, this operates under the assumption that the hay bale provides all the nutrient needs of the cow. It does not. Anticipate having to supplement protein on top of this to meet her protein requirements at an additional cost.

Protein

Protein is probably the most important macronutrient of the 3 (carbohydrates, fat, protein). It allows the cow to get better usage of the carbohydrates she does eat and can eventually be turned into energy storage when in excess. It is also happens to be the most expensive nutrient.

On a given day, native Bahia grass rarely meets the protein requirements of the cow. I usually expect my Bahia to give about 7% crude protein (CP). This varies throughout its growth stages, but 7-8% is a general rule of thumb. Keep in mind, Bahia is a warm-season grass, so winter growth is usually minimal to none.

The only time Bahia meets the demands of the cow is during the middle third of her gestation.

That means you have two choices to meet the protein demands of the cow – supplement (cubes, tubs, or liquid feed), or plant grasses with higher protein content and/or different growth pattern (Bermuda, Timothy, Legumes). This all comes at an additional cost.

Sidenote: Contrary to popular belief, application of nitrogen fertilizer does little to impact pasture protein content. It is used to increase the growth rate and subsequent dry matter production of the grass.

| Expected Crude Protein Requirements Adapted from Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle, 7th Edition, NRC, 2000 | |

| CP, % | |

| Mature, Non-Lactating Cow, mid 1/3 pregnancy | 7.1 |

| Mature, Non-Lactating Cow, last 1/3 of pregnancy | 7.9 |

| Growing, Non-Lactating Heifer, mid 1/3 pregnancy | 9.1 – 10.4 |

| Growing, Non-Lactating Heifer, last 1/3 pregnancy | 8.8 – 10.9 |

| Lactating Cow | 10.2 – 10.8 |

| Growing Calf (400 lbs) | 8.7 – 19 |

| Yearling (800 lbs) | 6.6 – 14 |

| Growing and Mature Bulls | 7 – 10 |

Calving Time

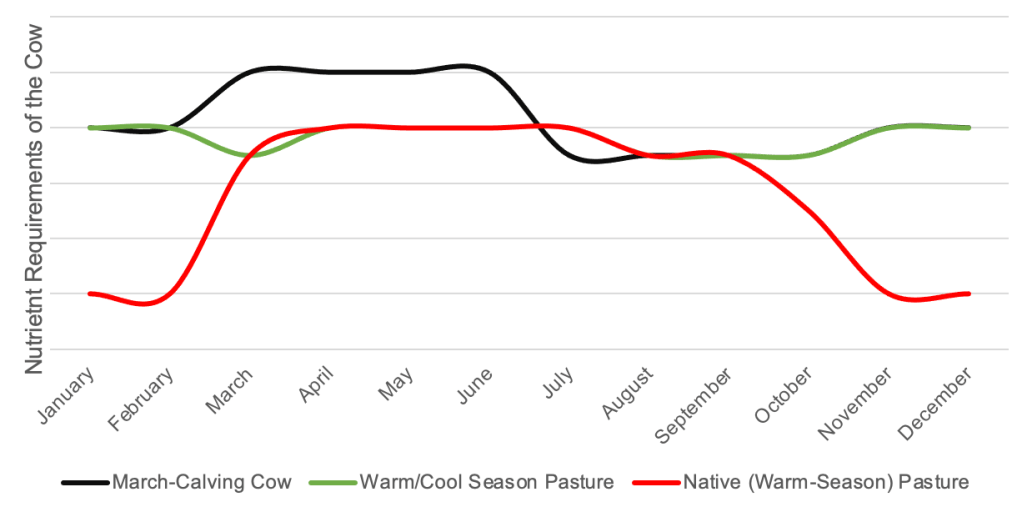

I would be remiss if I didn’t hit on the topic of matching the cow’s reproductive cycle to the seasonal changes of grass. Half of my Masters thesis was on this. Simply put, you match the cow’s greatest nutritional inputs (first 90 days of lactation after calving) when the pasture has the greatest nutritional output (growth/early-vegetative stage).

For example, in our Southeast Texas region, this would be a spring-calving cow that calves in March. This time frame would align her nutrition with the start of our warm-season, native grasses beginning their growth phase. As we enter the start of fall, when our native Bahia grasses enter their reproductive phase, the cow would be close to weaning her spring calf and ready to reduce her nutritional inputs. Ideally, pastures would have a cool-season annual or perennial grass mix to give adequate over-winter nutrition.

Here’s my attempt at putting this concept into a visual format, with both non-improved, predominantly warm-season pasture, and a cool/warm season mix pasture. The addition of cool-season grasses or legumes are an important factor in maintenance of the cow’s body condition over winter.

Type of Cow

Last, but not least, I’ll briefly hit on type of cow. There’s a few factors to consider

- Mature Cow Size/Weight

- Cow Age

- Cow Condition

As the mature cow size goes up, she requires more feed and nutrients to maintain. This means her AU goes up and pasture stocking rate goes down. She also tends to produce more milk and raise heavier calves. While these seem like good qualities, this needs to be balanced against your operation’s feeding capabilities.

The general age of your herd also impacts your stocking rate and nutrient demands. Young, growing heifers require more nutrient dense feed (think higher protein, more starches). As such, it is common to supplement these first-calf heifers. On the flip side, older cows (10+ years) may have worn teeth and struggle to keep their condition up.

Finally, there are the easy-keepers and the hard-doers. Some cows just keep up better than others. Some may call it a slow-metabolism (good in cows, bad in humans), but I think it has a lot more to do with her desire/ability to consume feed and her muscle to skeleton ratio. I’ve got 2 similar-age and size cows – one that gets fat off air and another who struggles to keep up without cubing. You’ll rarely catch the fat cow not eating, plus she is clearly the lighter muscled of the pair.

Leave a comment